In Australia, poetry related to scientific topics (‘science poetry’) is an emerging subgenre of writing. While poet Carol Jenkins has previously described the demographics of contemporary Australian poetry in the literature, no known quantitative research studies have focused on contemporary Australian science poetry. Therefore, our novel study aims to describe the demographics and characteristics of contemporary Australian science poetry. After independently reviewing twelve poetry or science writing anthologies to identify science poems, we jointly selected pieces for data collection. Categorical data on poem and poet characteristics were collected, with proportions in categories expressed as percentages and residential state/territory figures re-expressed per million population. The number of poets with science rather than non-science poems anthologised was statistically compared between genders using a chi-square test, with a p-value<0.05 denoting statistical significance. Across the anthologies, 100 science poems by 73 poets were identified. The most common poetry type and scientific discipline were free verse (93%) and biology (30%), respectively. Poets mostly used science to explore ideas of humanity and death. They were mainly female (55%) NSW residents (41%) with no formal science background (75%). The ACT had the most poets per million population (15). Women were significantly more likely to have science poems anthologised compared with non-science poems. Overall, our study of contemporary Australian science poetry provides a picture of an interdisciplinary genre and suggests avenues for future exploration.

Keywords: Australian poetry; science; creativity; interdisciplinary; demographics

The definition of a science poem

Up until the early 19th century, society viewed science and art as broad disciplines that overlapped and intersected with one another (Schatzberg 2012). Poetry is an example of an artistic discipline that has long shared a range of similarities with science. Science may be defined as ‘the systematic knowledge derived from observation, study and experimentation ([e.g.] the science of mathematics)’ (Grillo-López 2004: 941). Poetry, meanwhile, is ‘literature that evokes a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience or a specific emotional response through language chosen and arranged for its meaning, sound, and rhythm’ (Nemerov 2019: n.p.). Both poet and scientist observe, pose questions, experiment, create, analyse experience, fine tune work and exhibit attention to detail — a precision and exactness in the use of words or numbers. In 1817, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (cited in Tauber 2001) expressed a connection between the newer, more systematic form of observation (science) and the older, less systematic form of observation (poetry) when he wrote that people ‘forgot that science arose from poetry, and did not see that when times change the two can meet again on a higher level as friends’ (137). When commenting on the beauty of science, physicist Richard Feynman (1964: 3-6) wondered ‘Why do the poets of the present not speak of it?’ Mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya (1895: 316), meanwhile, stated that ‘It is impossible to be a mathematician without being a poet in soul.’

Despite their similarities, over time poetry and science have grown apart and developed distinct characteristics. These different characteristics can complement one another. Characteristics of science that can enrich poetry include inductive reasoning, logic, pragmatism, visual images (e.g. microscopic photos and data visualisations), scientific concepts and terminology (Leach & Rayner 2018). In particular, the precise terminology of science offers poets a rich vocabulary of specific, interesting, often multisyllabic words, as exemplified by Australian scientists-turned-poets Tricia Dearborn (2019), Ian Gibbins (2012) and Carol Jenkins (2008). Characteristics of poetry that can enrich science, meanwhile, include aesthetics, intuition, emotions, distillation of thought and a wide range of poetic devices (Leach & Rayner 2018). Novelist Raymond Chandler (1978: 7) captured the essence of this potential complementarity in his line ‘The truth of art keeps science from becoming inhuman, and the truth of science keeps art from becoming ridiculous.’

When science and poetry unite, the product may be thought of as a ‘science poem’. Such poems can be delightful, charming, intriguing, novel, memorable, mystifying and eye-opening. An interdisciplinary approach to writing and creativity is a prerequisite to writing a science poem, as select poets’ works will illustrate throughout this paper.

A search of the literature for a formal definition of a science poem revealed a notable gap. No definitions for science poetry were found in peer-reviewed journals. In Australia, Writing NSW (2018: n.p.) provided a broad definition within its description of the Quantum Words 2018 Science Poetry Competition, stating that ‘Poems must include or address some aspect of science, but apart from that, your imagination is the limit.’ Internationally, the most detailed definition for a science poem was found within a Master of Science in Science Education thesis written by an American student:

A poem which is inspired by and/or informed by scientific facts, phenomena, principles, questions, observations, and experiences.

A poem which utilizes quantitative and qualitative data to describe scientific phenomena, principles, questions, and observations and experience.

A poem which is science-subject based, utilizing scientific vocabulary, concepts, principles and knowledge. The poem appears to be about science at first, but then ‘leaps’ to say something more.

(Colfax 2012: 53; author’s emphasis)

While we agree with this definition, we feel it could be refined through reference to the work of others.

As indicated by Colfax’s definition, some poems can be classified as a science poem through usage of an extended vocabulary alongside a close observation of the world as if through a microscope:

External bacillus like Clostridium (tetanus, botulism, gangrene)

found up or down the garden path, in damp fields and on executive surfaces

burglarise you with a 600 piece toolkit slicing your biopolymers into simple

mounds of rubble.

(Bennett 2016: 39; reproduced with the written permission of the poet)

The mention of a scientific term or discipline in isolation does not automatically make a piece of poetry a science poem. For instance, a poem that mentions the word ‘physics’ would not necessarily be a science poem if it does not directly engage with scientific concepts. Furthermore, in order to be classified as science poetry, a poem should correctly use scientific terminology or concepts. In his 1959 Rede Lecture The Two Cultures, CP Snow (2008: 16) cautioned against using scientific language as the sole requirement for a science poem:

Now and then one used to find poets conscientiously using scientific expressions, and getting them wrong — there was a time when ‘refraction’[1] kept cropping up in verse in a mystifying fashion, and when ‘polarised light’ [2] was used as though writers were under the illusion that it was a specially admirable kind of light. Of course, that isn’t the way that science could be any good to art. It has got to be assimilated along with, and as part and parcel, of the whole of our mental experience, and used as naturally as the rest.

Some poems are rather subtle in their existence as science poetry; it can be themes rather than terminology that address our relationship to science. Meredi Ortega’s brief poem atoms does just this:

one day we may have to explain

how from stars we made

tins of beans

tubes of toothpaste

diamond rings, light bulbs, people

and how we took out all the shine

(Ortega 2010: 19; reproduced with the written permission of the poet)

Through the unusual coupling of grand cosmic objects with humble household items, Ortega has brought into focus the origin story of all elements on Earth (and the Earth itself) without using scientific terminology.

While recognising the ideological difficulties in defining identities and the risk of broadening a divide between art and science, we have arrived at our own definition based on both Colfax’s definition and our analysis of poems already described by others as science poetry:

A science poem is any verse in which the author has correctly used scientific terminology, concepts, principles or knowledge to provide an analytical view of the world or surrounding universe. The poem could be related/responding to stimuli or reflecting the scientific method in some way.

Importantly, the poem need not be about science. Instead, it may use science to further the expression of the writer.

The scientific terminology or concepts in science poems may be drawn from different disciplines, including biology, chemistry, geology, health sciences, mathematics and physics. Each of these broad scientific disciplines is defined in Table 1.

Table 1: Definitions of broad scientific disciplines (Encyclopædia Britannica 2019: n.p.)

|

Scientific Discipline |

Definition |

|

Biology |

‘the study of living things and their vital processes’ |

|

Chemistry |

‘the science that deals with the properties, composition, and structure of substances (defined as elements and compounds)’ |

|

Geology |

‘the fields of study concerned with the solid Earth’ |

|

Health science |

the study of ‘the extent of an individual's continuing physical, emotional, mental, and social ability to cope with his or her environment’ |

|

Mathematics |

‘the science of structure, order, and relation that has evolved from elemental practices of counting, measuring, and describing the shapes of objects’ |

|

Physics |

the science that ‘deals with the structure of matter and the interactions between the fundamental constituents of the observable universe’ |

Our definition of ‘contemporary poetry’ is any verse first published from 1990 onwards, following the conditions used by the editors of Contemporary Australian Poetry (Langford, Beveridge, Johnson and Musgrave 2016).

Sources of contemporary Australian science poetry

Science poetry, as defined here, is an emerging subgenre of writing in Australia. Examples by Australian authors are available in journals such as the Medical Journal of Australia and GRAVITON as well as various poetry collections, including:

- Autobiochemistry (Dearborn 2019), Frankenstein’s Bathtub (Dearborn 2001) and The Ringing World (Dearborn 2012)

- A Skeleton of Desire (Gibbins 2018), The Microscope Project: How Things Work (Gibbins 2014) and Urban Biology (Gibbins 2012)

- A Crooked Stile (Jenkins 2019a), Fishing in the Devonian (Jenkins 2008) and Xn (Jenkins 2013)

Science poems are also encountered in oral form at literary events, such as the Quantum Words festivals held by Writing NSW and Writing WA, as well as through public exhibitions, displays and multimedia experiences. South Australian poet gareth roi jones’ poem Many-Worlds Quantum Mechanics vs Earth-based Grease Monkeys first appeared as a public display on a science building in Adelaide (Jones 2012). Victorian poet Alicia Sometimes (2019) utilises multimedia experiences with recorded science poetry readings in her touring shows Elemental and Particle/Wave.

A key source of science poems is anthologies, which are likely to capture multiple diverse voices addressing a range of topics. Examples of Australian anthologies that are known to include contemporary science poems are the Science Made Marvellous series, The Best Australian Science Writing series and Contemporary Australian Poetry. The Science Made Marvellous series, created for National Science Week 2010, comprises three books of discipline-specific science poems that were selected and published by two editors and a project editor with the support of the Australian Government (Emery and Haritos 2010a-2010c). The Best Australian Science Writing series is an annual anthology of selected science texts produced by Australians in the previous year (Pincock 2011, Finkel 2012, McCredie and Mitchell 2013, Hay 2014, Nogrady 2015, Chandler 2016, Slezak 2017, Pickrell 2018). Of the 253 pieces published in Best Australian Science Writing 2011-2018, 14 (5.5%) are poetry rather than prose. Contemporary Australian Poetry, meanwhile, is a major anthology of poems selected by four editors via consensus decision making (Langford et al. 2016).

The rationale and aim of our research

In a novel demographic study published by the Australian Poetry Journal, Australian poet and scientist Carol Jenkins (2016) described the demographics of contemporary Australian poetry. After collecting data on 335 poets who collectively published 651 poems across nine Australian anthologies, she found a lack of gender parity: 58% of anthologised poets were male.

While Jenkins’s study has shed light on the demographics of contemporary Australia poetry in general, no known studies have previously described the demographics and characteristics of contemporary Australian science poetry as a representative sample of the whole. In order to fill this gap in the literature and inform further discussion, research and poetic practice, we aimed to describe contemporary Australian science poetry and poets published in anthologies.

The method of our research

We adopted a similar approach to Jenkins by conducting a review of Contemporary Australian Poetry and the eleven anthologies in the Science Made Marvellous and The Best Australian Science Writing series. The chosen anthologies were brought to our attention by expert panels at two literary events: the ‘Poetic State’ panel at Bendigo Writers Festival 2017 and ‘The Poetry of Science’ panel at Quantum Words 2018. Different types of Australian anthologies — science writing, science poetry and contemporary poetry — were used to increase sample size and representativeness while not favouring any one type of anthology featuring Australian science poetry. While we were unsure what to expect for poetry type and scientific topic, we hypothesised that most contemporary Australian science poets would be male (based on Jenkins’s study) residents of New South Wales (NSW) (based on population size and state of publication of the anthologies) with formal scientific backgrounds (based on our a priori knowledge that three prominent science poets — Dearborn, Gibbins and Jenkins — studied science at a tertiary level).

When undertaking our review, we independently read the anthologies and selected poems matching our definition of a science poem. We subsequently compared and discussed our selections to arrive at a consensus on the final group. To better understand how science and poetry interact, along with science poets’ methods for creativity, three poem characteristics were recorded: primary scientific discipline (e.g. biology), specific scientifically-relevant topic (e.g. bacteria) and poetry type. While not seeking particular poetry types, we did specify five categories: free verse, concrete poetry, prose poetry, found poetry and formulaic poetic forms (e.g. sonnets). Additionally, published biographies were used to determine three poet characteristics: gender as identified through pronoun use (i.e. he, she or they); formal scientific background as indicated by a qualification or employment history in science; and the residential state or territory at the time of anthology publication.

Poem-level data were used to calculate the proportions (percentages) of poems in each category of poem characteristics while poet-level data were used to calculate the proportion (percentage) of poems in each category of poet characteristics. The specific scientifically-relevant topics addressed across the selected poems were visualised through a word cloud produced in NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia). For comparative purposes, the average annual Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) population estimates over 2010-2018 were used to calculate the number of Australian poets with anthologised contemporary science poems per 1,000,000 population resident in each state or territory (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019). In order to compare the gender breakdown in our sample, the gender of poets featured in Contemporary Australian Poetry who had no science poems published across any of the twelve anthologies was collected and quantified. The number of poets who had science rather than non-science poems anthologised was compared between males and females using the chi-square test for independence, with a p-value<0.05 indicating statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS Version 24 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington State, USA).

The results and discussion

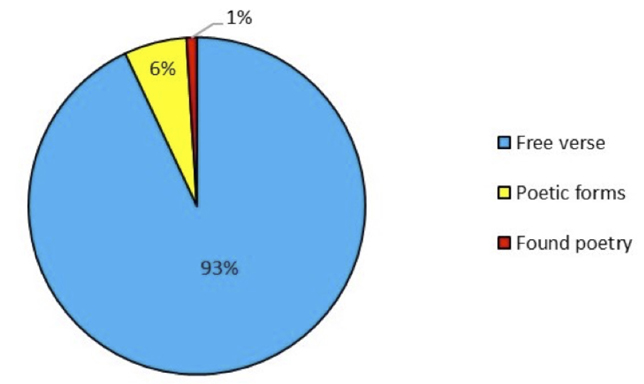

Across the twelve reviewed anthologies, 100 contemporary science poems by 73 Australian poets were identified. The vast majority (93%) of the science poems were written in free verse (Figure 1). This result fits with the fact that free verse is the favoured form of the past century, as supported by the full contents of Contemporary Australian Poetry (Langford et al. 2016). Owing to the 20th century’s dramatic shift in concepts of what constitutes art, traditional poets such as Adam Lindsay Gordon would likely find the current poetry landscape unrecognisable. Strict poetic forms have given way to a freedom of language and expression rooted in everyday life.

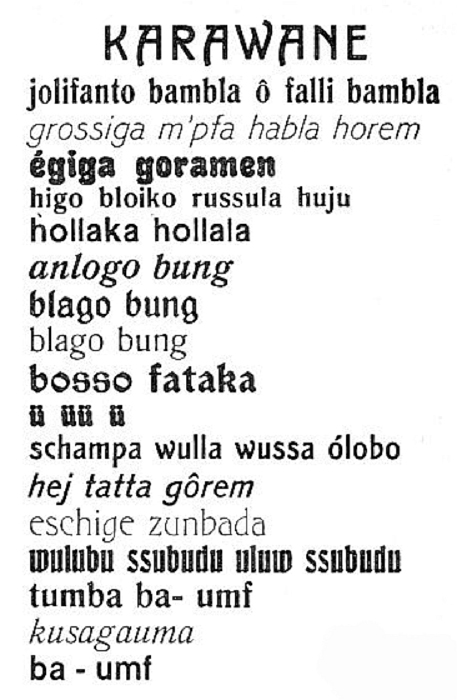

Though free verse had entered English poetry at the turn of the 20th century from the French vers libre that emerged in the 1880s (Encyclopædia Britannica 2019), Shipe (2012: n.p.) has pointed out that ‘Contemporary art as we know it could not have come into existence without Dada.’ In the early 20th century, the Dada poets were actively freeing and unravelling language. This arguably became a driver of creativity and expression, enabling more complex dialogues between different emotions, experiences and, of particular relevance to this paper, disciplines (Trachtman 2006). Sounds, nonsense and the statistical element of chance were introduced into a poet’s toolkit. Hugo Ball’s (2006) abstract poem written in 1917, ‘Karawane’, is built on sounds that transcend linguistic divides (Figure 2). This was an open challenge to the prevailing notions of artistic creation centred on rules.

Through Dada and other modernist movements, poets have opened up poetry to exploration by breaking away from rhyme, metre and traditional forms. Free verse is the culmination of relaxed rules and playful language combinations. In science poetry, this drives an infusion of scientific terminology that can stir intense imagery and movement, as in this excerpt from Jenkins’s poem Cloud Me:

I read as thirty-eight litres of cloud potential,

thirty-eight litres of ebullient cumulus rising,

lapping through the water cycle I will be nimbus,

stratus, cirrus, altos, storm and ice.

(Jenkins 2010: 24; reproduced with the written permission of the poet)

Jenkins (2019b) describes Cloud Me as a free verse poem with some slant rhymes set out in tercets [4]. The almost exclusive use of free verse among contemporary Australian science poets may be partly attributable to this poetry type’s high degree of science-like experimentation, which is useful for interdisciplinary writing.

By comparison, found poetry — which was first referenced in 1966 (Merriam-Webster 2019) — was used in only 1% of anthologised Australian science poems (Figure 1). In a found poem, words are borrowed directly from any source, whether street signs or scientific textbooks, with appropriate referencing (Joseph 2019). This poetry type is created through the unearthing of a poem from an existing text, in contrast to free verse’s unconstrained experimentation. Joseph (2019) identified three subtypes of found poetry: free-form, erasure and research. A free-form found poem takes words from another source and redeploys them in any order, as in the below excerpt from a poem that Noordhuis-Fairfax (2015: 51) unearthed from a photography reference book (Sowerby 1956):

Attempts were made to construct light.

It is possible, but by no means easy, to prepare

something clear, bright.

Troubles may arise if solutions with fancy names

fade in the dark or are found to have an irritating brilliancy.

Reproduced with the written permission of the poet.

An erasure found poem involves taking a text and erasing most of the words until a piece of poetry emerges. Research found poetry — ‘a form growing particularly in the qualitative data gathering sphere’ (Joseph 2019: n.p.) — has been applied mostly in the social sciences, including psychology and nursing, but has scope for broader scientific applications. Patrick (2013: 54) states that ‘research poetry is written from and about research subjects…’ to provide ‘…an alternative means for both analysing and representing qualitative data’. While free-form found poetry was observed in our sample, neither erasure nor research found poetry were represented.

Concrete poetry is verse imbued with an added element of meaning through the shaping of words into a relevant image. This is a broad poetry type that can become visual art, thereby offering poets many possibilities. We were surprised to find no concrete science poems across the twelve anthologies. With multitudinous visualisations necessary in scientific disciplines (e.g. the display of information in graphs, the photography of samples and recordings of asteroid tracts), it could be argued that concrete poetry has the potential to illuminate scientific topics. Between us, we have used concrete poetry to visually depict the movement of paracetamol through the human body over time (Leach 2017), to help communicate the impact of climate change on the life cycle of the Adélie penguin (Leach 2019) and to present a limerick about the Higgs boson particle in the shape of a Feynman diagram (Rayner & Leach 2019). It is unclear why there were no concrete poems in our sample. [3]

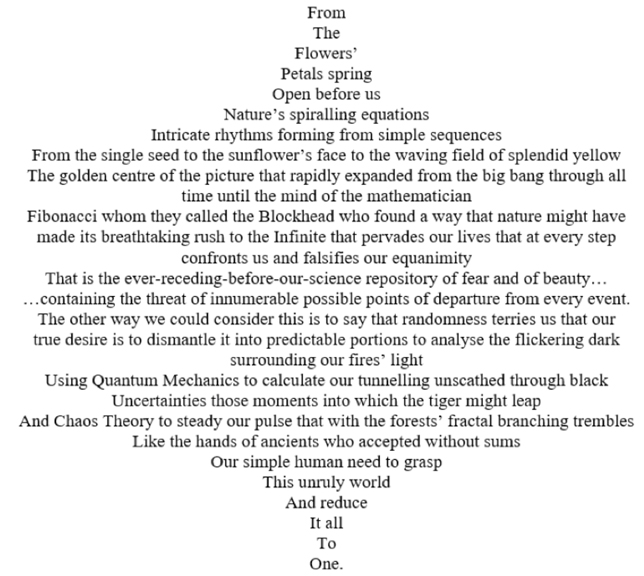

The final poetry type observed, poetic forms, made up 6% of the contemporary Australian science poetry sample. These mostly traditional forms use strict structures and identifiable patterns, much like investigative science, and have been adapted to scientific contexts. Use of the ‘sciku’ (science haiku [5]) is increasing, with a dedicated online anthology (Holmes 2019) and an interactive periodic table (Lee 2017). Reviewing Australian anthologies, however, did not locate any science poems in this succinct form. One poem was in the traditional Japanese form ‘tanka’ [6] while others took on Western forms including the sonnet and the ode. Strict poetic forms following unshifting rules have also been developed from innovative mathematical sources, as in Tim Metcalf’s (2010: 27-28) Fibonacci poem. In this poetic form, the syllable pattern matches the Fibonacci sequence of 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55,... (Figure 3). Each aspect of nature described in Metcalf’s poem also reflects the naturally-occurring and recurring Fibonacci sequence: both content and constraint are inherently mathematical. As this poem is based on biomathematics, which universities classify as mathematics rather than biology, its primary scientific discipline has been classified as mathematics in our study.

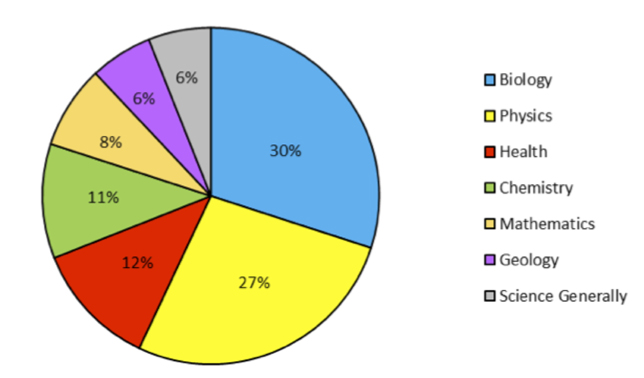

Biology was the most commonly observed primary scientific discipline among contemporary Australian science poets, comprising 30% of the poetry sample (Figure 4). This discipline has long been the most popular science subject (other than mathematics) among Australian year twelve students (Kennedy, Lyons and Quinn 2014). Biology may be more relatable than other sciences as human beings constantly interact with the natural world through such activities as maintaining gardens, looking after pets and generally perceiving our bodies as biological agents rather than physical or chemical ones. The very idea of life, with all its uncertainty and conflict, is inherently poetic (Heinrich 1999).

The next most common scientific discipline among contemporary Australian science poets, accounting for 27% of the sample, was physics (Figure 4). Physics and poetry are both abstract disciplines that seek to understand the essence of our world and the universe. The complexity of physics may be captured and distilled through metaphorical language while natural physical phenomena can inspire the kind of wonder that may only be adequately expressed in verse (Matlock 2017).

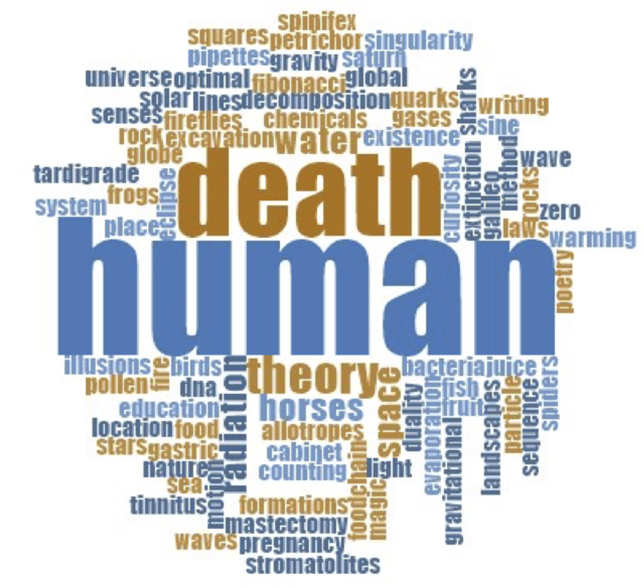

In addition to primary scientific disciplines, we obtained data on specific scientific-related topics (Figure 5). Science poetry is primarily created to explore the human condition and our relationship with death. Science, it seems, offers an extra level of language with which to explore our shared humanity. In terms of animals, the topic ‘horses’ was addressed in 3% of anthologised Australian science poems. Some physics concepts were also relatively common, including ‘space’ and ‘stars’.

When examining science poetry topics, a question forms regarding the poets’ sources of inspiration and from where their desire to use scientific concepts arises. Our hypothesis that most identified science poets would have a formal science background is not supported by the data collected for this review. The incorporation of scientific topics into poetry often does not correspond to scientific education or employment, as three-quarters of the 73 anthologised Australian science poets do not have a formal science background. This means that inspiration does not always stem from formal education or practice. Rather, it reflects the creative mind’s natural tendency to seek sources of inspiration beyond one’s primary discipline, as when taking a study break or working in a multidisciplinary team (Harford 2018). The unexpectedly low proportion of poets with a formal scientific background may be related to the idea that, the more one knows about a subject, the more difficult it can be to write about it imaginatively (Coles, Pang, Gardener and Beveridge 2019). As knowledge of a given scientific topic is an asset when writing a science poem, those without a formal science background in our study may have researched scientific topics of interest. US poet Mary Soon Lee emphasised the importance of research when providing tips for aspiring science poets (2019b). The three-quarters of contemporary Australian science poets without a formal background in science may be thought of as ‘citizen science communicators’ whose work crosses traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Among the 73 anthologised contemporary Australian science poets, there were slightly more females (40 or 55%) than males (33 or 45%) and no non-binary individuals. It could be that editors of Science Made Marvellous and The Best Australian Science Writing took care to maintain approximate gender balances as part of good practice. It is also possible that science poetry is more often written by women. Indeed, the Poetry on the Move 2019 panel entitled ‘The Science of Poetry’ featured only female panellists (Dearborn, Coles, Elvey and Lovell 2019). When the proportion of females in our sample who had science poems anthologised (55%) was compared with the proportion of females among 200 other poets who had non-science poems anthologised (40%), a statistically significant difference was found (p-value = 0.024). The gender breakdown observed in our sample also contrasts with the proportions reported in a prior study of 335 contemporary Australian poets whose poetry on any topic had been anthologised (Jenkins 2016). In this past sample, as in our comparison group, there were more males (58%) than females (42%). Our result regarding the gender of science poets, therefore, is unexpected in terms of an internal comparison, past literature and our hypothesis. While only 16% of all Australians with university or vocational education and training qualifications in science are female (Office of the Chief Scientist 2016), there is no such gender imbalance with respect to science poetry publishing in Australian anthologies. The reasons for this could be explored in future studies.

When considering the number of contemporary Australian science poets residing in each state or territory, the observed geographic distribution of poets came as a surprise (Table 2). The equal number of science poets residing in South Australia (SA) and Victoria was unexpected as the latter state has a population approximately 3.5 times larger than the former (Table 2). As predicted, NSW has the highest number of resident science poets. This result is highly likely as NSW is the most populous state or territory in Australia, all the reviewed anthologies were published in Sydney and three-quarters of the 16 anthology editors reside in NSW. Our quantitative assessment of which state or territory had the most poets per capita delivered another surprise: the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) had more poets per million population than any other state or territory by a factor of at least 2.1 to 1 (Table 3). This may be because the proportion of people educated beyond year twelve is higher in the ACT than in any other Australian state or territory (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018) and/or there is a strong network of ACT poets and consumers of poetry. SA had the second highest number of science poets per capita, whereas NSW had the equal fourth highest number per capita (Table 3).

Table 2: Proportion of anthologised Australian science poets residing in each Australian state/territory (n = 73)

|

Residential state/territory |

Number |

Proportion |

|

New South Wales |

30 |

41% |

|

South Australia |

11 |

15% |

|

Victoria |

11 |

15% |

|

Western Australia |

7 |

10% |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

6 |

8% |

|

Queensland |

4 |

5% |

|

Tasmania |

3 |

4% |

|

Northern Territory |

1 |

1% |

Table 3: Number of anthologised Australian science poets residing in each Australian state/territory per 1,000,000 resident population

|

Residential state/territory |

Number |

State/territory population* |

Number of poets per 1m resident population |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

6 |

390,028 |

15 |

|

South Australia |

11 |

1,683,994 |

7 |

|

Tasmania |

3 |

515,683 |

6 |

|

Northern Territory |

1 |

240,757 |

4 |

|

New South Wales |

30 |

7,531,628 |

4 |

|

Western Australia |

7 |

2,482,261 |

3 |

|

Victoria |

11 |

5,921,708 |

2 |

|

Queensland |

4 |

4,709,375 |

1 |

* average between 2010 and 2018 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019)

Conclusion

In this paper, we have defined science poetry and described it in the Australian context. Our results show that the poetry type of choice among contemporary Australian science poets is free verse, which provides scope for progressive experimentation. The science poets in our sample mainly chose to write about biology and, to a lesser extent, physics. The topics addressed illustrate how poetry uses science to explore humanity and capture our shared experiences, from life to death. There were no non-binary individuals and somewhat more women than men in our sample of 73 contemporary Australian science poets, with females being significantly more likely to have science poems anthologised compared with non-science poems. The reasons for this are unknown, providing an avenue for future research. Three-quarters of contemporary Australian science poets had no formal scientific background and, thus, may be thought of as citizen science communicators who communicate scientific topics. While the most common state or territory of residence among poets in our sample was NSW at 41%, the top residential location on a per capita basis was the ACT with 15 poets per million population. The profile of contemporary Australian science poetry and poets presented here provides a high-level picture of a growing interdisciplinary genre that has the potential to help bridge the ‘two cultures’ of the sciences and the humanities. This picture could be further explored and built upon in the future.

Notes:

1 Refraction is the change of a wave’s direction as it passes through different materials — most commonly observed in light (though sound waves and water ripples are other examples). This direction change is less than for reflection, where the wave bounces back in the direction it came in.

2 Polarised light occurs when light travels through a polarising filter. This filter will only allow light from one direction to pass through, blocking out the rest. This usually results in a darker image or — in the case of our sunglasses — reduced glare.

3 Exploring the reasons for a lack of concrete poetry among anthologised contemporary Australian science poems is beyond the scope of this paper. The same can be said for prose poetry. It could be that concrete poetry and prose poetry are niche types of Australian science writing, editors had a preference against using them (potentially due to typographical challenges or publishing constraints), or none were worthy of anthologisation.

4 A tercet is ‘a set or group of three lines of verse rhyming together or connected by rhyme with an adjacent triplet’ (Lexico 2019: n.p.).

5 A haiku is a particularly succinct poem with the typical form five-seven-five onji or small Japanese metrical units, which English syllables approximate. Traditional haiku reflect the seasons and nature (Higginson 2003: 289).

6 A tanka is a traditional ‘lyrical poem with the typical form five-seven-five-seven-seven onji’ or small Japanese metrical units, which English syllables approximate (Higginson 2003: 294).

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018 ‘6227.0 — Education and work, Australia, May 2018’, at

https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/6227.0Main+Features1May%202018?OpenDocument (accessed 28 September 2019)

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019 ‘3101.0 — Australian demographic statistics, Sep 2018’, at

https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3101.0Sep%202018?OpenDocument (accessed 25 September 2019)

Ball, H 2006 ‘Karawane’, at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hugo_ball_karawane.png (accessed 28 September 2019)

Bennett, J 2016 ‘from True love: for B.’, in M Langford, J Beveridge, J Johnston and D Musgrave (eds) Contemporary Australian poetry, Glebe NSW: Puncher & Wattmann, 39-40

Chandler, J (ed) 2016 The best Australian science writing 2016, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Chandler, R 1978 ‘Great thought’, in The notebooks of Raymond Chandler, New York, NY: Ecco Press

Coles, K, Pang, A, Gardner, A and Beveridge J 2019 ‘Poetry and process’, panel at Poetry on the Move 2019, Canberra, at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/b2bcbf_b7072a04b8874ce7885f06ff27b6a494.pdf (accessed 23 October 2019)

Colfax, E 2012 The impact of infusing science poetry into the biology curriculum, Bozeman, MT: Montana State University

Dachy, M 2005 Dada: The revolt of art, London: Thames & Hudson

Dearborn, T 2001 Frankenstein’s bathtub, Cairndale QLD: Interactive Press

Dearborn, T 2012 The ringing world, Glebe NSW: Puncher & Wattmann

Dearborn, T 2019 Autobiochemistry, Crawley WA: UWA Publishing

Dearborn, T, Coles, K, Elvey, A and Lovell, B 2019 ‘The science of poetry’, panel at Poetry on the Move 2019, Canberra, at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/b2bcbf_b7072a04b8874ce7885f06ff27b6a494.pdf (accessed 23 October 2019)

Emery, B and Haritos, V (eds) 2010a Earthly matters: biology and geology poems, Potts Point NSW: The Poets Union Inc.

Emery, B and Haritos V (eds) 2010b Holding patterns: physics and engineering poems, Potts Point NSW: The Poets Union Inc.

Emery, B and Haritos V (eds) 2010c Law and impulse: maths and chemistry poems, Potts Point NSW: The Poets Union Inc.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2019 ‘Encyclopædia Britannica’, at https://www.britannica.com/ (accessed 28 July 2019)

Feynman, R 1964 ‘The relation of physics to other sciences’, in R Feynman (ed) The Feynman lectures on physics, Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley

Finkel, E (ed) 2012 The best Australian science writing 2012, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Gibbins, I 2012 Urban biology, Norwood SA: Friendly Street Poets

Gibbins, I 2014 The microscope project: how things work, Bedford Park SA: Flinders University Art Museum

Gibbins, I 2018 A skeleton of desire, Magill SA: Garron Publishing

Grillo-López, AJ 2004 ‘The ODAC Chronicles — Part 2. Statistics and clinical medicine in the USA: the triumph of science over art’, Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 4, 941-944

Harford, T 2018 ‘A powerful way to unleash your natural creativity’, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yjYrxcGSWX4 (accessed 7 October 2019)

Hay, A (ed) 2014 The best Australian science writing 2014, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Heinrich, B 1999 Mind of the raven: investigations and adventures with wolf-birds, New York, NY: Cliff Street Books

Higginson, W and Harter, P 2003 The haiku handbook, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Holmes, AM 2019 ‘The sciku project’, at https://thescikuproject.com/ (accessed 15 September 2019)

Jenkins, C 2008 Fishing in the devonian, Sydney NSW: Puncher & Wattmann

Jenkins, C 2010 ‘Cloud Me’, in B Emery and V Haritos (eds) Holding patterns: physics and engineering poems, Potts Point NSW: The Poets Union Inc.

Jenkins, C 2013 Xn, Glebe NSW: Puncher & Wattmann

Jenkins, C 2016 ‘A gander at gender and age: the demographics of contemporary Australian Poetry’, Australian Poetry Journal 6, 12-20

Jenkins, C 2019a A crooked stile, Glebe NSW: Puncher & Wattmann

Jenkins, C 2019b ‘Carol Jenkins’ poetry’, personal email communication to R Rayner

Jones, GR 2012 ‘Many-worlds quantum mechanics vs earth-based grease monkeys’, public display on RiAus building, Adelaide, South Australia

Joseph, S 2019 ‘Locating poems inside the quotidian: finding poetry in ordinary language’, Axon 9 (1), at https://www.axonjournal.com.au/issue-vol-9-no-1-may-2019/locating-poems-inside-quotidian (accessed 21 July 2019)

Kennedy, J, Lyons, T and Quinn, F 2014 ‘The continuing decline of science and mathematics enrolments in Australian schools’, Teaching science, 60 (2), 34-46

Kovalevskaya, S 1895 Sónya Kovalévsky: her recollections of childhood, New York, NY: The Century Co.

Langford, M, Beveridge, J, Johnson, J and Musgrave, D (eds) 2016 Contemporary Australian poetry, Glebe NSW: Puncher & Wattmann

Leach, M 2017 ‘The pharmacokinetics of paracetamol’, in Cordite poetry review 83, at

http://cordite.org.au/poetry/mathematics/the-pharmacokinetics-of-paracetamol/ (accessed 25 October 2019)

Leach, MJ 2019 ‘The plight of the Adélie penguin’, in The Antarctic poetry exhibition, at

https://www.antarcticpoetry.com/michael-leach-adelie-penguin (accessed 25 October 2019)

Leach, M and Rayner, R 2018 ‘Writing poetry scientifically or science poetically’, at

http://2018conf.asc.asn.au/writing-poetry-scientifically-or-science-poetically/ (accessed 12 July 2019)

Lee, MS 2017 ‘Elemental haiku’, at http://vis.sciencemag.org/chemhaiku/ (accessed 25 October 2019)

Lee, MS 2019 ‘On writing elemental haiku — Mary Soon Lee interview, part one’, at

https://thescikuproject.com/2019/09/30/mary-soon-lee-interview-part-1/?fbclid=IwAR0DWTx-f7Sq-6U5w2Zfj-tHshRZn__kel3n6s8OXsiDy6JaxI_HfBlfYF4 (accessed 30 September 2019)

Lexico 2019 ‘Tercet’, at https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/tercet (accessed 6 October 2019)

Matlock, S 2017 ‘Quantum poetics’, The New Atlantis, 53, 47-67

McCredie, J and Mitchell, N (eds) 2013 The best Australian science writing 2013, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Merriam-Webster 2019 ‘Found poem’, at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/found%20poem (accessed 4 October 2019)

Metcalf, T 2010 ‘1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34,55,...’, in B Emery and V Haritos (eds), Law and impulse: maths and chemistry poems, Potts Point NSW: Poets Union Inc., 27-28

Nemerov H. ‘Poetry’ Encyclopædia Britannica, at https://www.britannica.com/art/poetry (accessed 2 May 2020)

Nogrady, B (ed) 2015 The best Australian science writing 2015, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Noordhuis-Fairfax, S 2015 ‘Light’, in B Nogrady (ed), The best Australian science writing 2015, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 51-52

Office of the Chief Scientist 2016 Australia’s STEM workforce: science, technology, engineering and mathematics, Canberra: Australian Government

Ortega, M 2010 ‘atoms’, in B Emery and V Haritos (eds), Law & impulse: maths & chemistry poems, Potts Point NSW: The Poets Union Inc., 19

Patrick, L 2013 Found poetry: a tool for supporting novice poets and fostering transactional relationships between prospective teachers and young adult literature, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University

Pickrell, J (ed) 2018 The best Australian science writing 2018, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Pincock, S (ed) 2011 The best Australian science writing 2011, Sydney NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Rayner, R 2018 ‘The artistry of science poetry’, in National Arts Festival 2018, at

https://www.nationalartsfestival.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2018-Programme-21_05.pdf (accessed 12 July 2019)

Rayner, R and Leach, M 2019 ‘Higgs in Feynman’, in FIVE:2:ONE, at

http://five2onemagazine.com/higgs-in-feynman-collaborative-poetry-by-michael-leach-and-rachel-rayner/ (accessed 25 October 2019)

Schatzberg, E 2012 ‘From art to applied science’, Isis 103, 555-563

Shipe, T 2012 ‘The international Dada archive’, at http://sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu/dada/history.htm (accessed 1 September 2019)

Slezak, M (ed) 2017 The best Australian science writing 2017, Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing

Snow, CP 2008 The Two Cultures, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sometimes, A 2019 ‘Alicia Sometimes’, at http://www.aliciasometimes.com/ (accessed 12 August 2019)

Sowerby, ALM 1956 Dictionary of photography, London: Iliffe and Sons

Tauber, AI 2001 ‘Henry David Thoreau and the Moral Agency of Knowing’, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, at

https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=kt796nc8hb;chunk.id=0;doc.view=print (accessed 2 May 2020)

Trachtman, P 2006 ‘A brief history of Dada’, at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/dada-115169154/#LL31gWEq1F0rZy1b.99 (accessed 1 September 2019)

Writing NSW 2018 ‘Quantum words 2018 science poetry competition’, at

https://writingnsw.org.au/support/funding-opportunities/quantum-words-science-poetry-competition/ (accessed 8 August 2019)